I have always been interested in the way writers choose to represent emotion in their work, especially in those moments of transition in a character’s life. Personally, I wondered how someone could represent pivotal moments with such clarity. What exactly did one need to present a moment of transition with the correct tone, emotionality, and hint of futurity that created a scene everyone understood? At what point does a scene go from being just a scene, to being a transitional moment in which readers understand its implied importance?

In this essay, I examine how the restructuring of self-identity is represented in Marjane Satrapi’s The Complete Persepolis, Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’s This One Summer, and Shūzō Oshimi’s Happiness, and I argue that the bleed pages in which these moments occur connect the possible self with landscape to create a timeless moment of implied understanding of importance.

So, what is “the possible self”?

In the article “Possible Selves”, Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius present the idea of the possible self (954). They discuss the importance of knowing oneself, and how this knowledge adjusts how individuals think about their future and their potential. The concept of the possible self signifies an individual’s thoughts on what they would like to be, what they can be, and what they are afraid of being:

“Possible selves derive from representations of the self in the past and they include representations of the self in the future. They are different and separable from the current or now selves, yet are intimately connected to them” (954).

When a character is connected to the concept of the possible self, it provides context for the past and incentives for the future, creating a complex emotional map to understanding; this theory can be applied when analysing the restructuring of self-identity.

What does this mean for The Complete Persepolis, This One Summer, and Happiness?

For each of the main characters in The Complete Persepolis, This One Summer, and Happiness, the understanding of their possible self is the catalyst for their emotional development and is represented alongside landscape in bleed pages to create scenes of importance. These scenes highlight to the reader the nuanced hopes, fears, worries, and fantasies of the characters through the development of their possible self. Based on this research, each of these comics invites readers to understand and consider the characters’ developing understanding of their possible selves.

The Complete Persepolis, This One Summer, and Happiness, present landscapes which represent character’s emotional states by depending on the implied concept of familiarity and the reader’s interpretation of the landscape, not on the reality of it, and is used to define a character’s changing identity.

Landscapes as emotional representation

In the article “Landscape: The Problem of Representation”, Virve Sarapik discusses the styles of landscape representation and the differences between them, ultimately highlighting the pros and cons between styles. Sarapik states that each representation of landscape is connected by one similarity: the use of landscape as a cognitive theory, where

“on one hand [it is] related to the information received via sensory perception, and on the other hand, to certain conventions” (184).

The article argues that landscape is a semiosis which embodies the relationship between the signified and the signifier (187); in short, the landscape is the signifier of the character (the signified) which it is built around.

The article discusses styles of representation, wherein landscape is inaccurately represented thereby widening its representation of ideas, feelings, and fantasies, yet also claims that realistic depictions of landscape are relative and meaning originates from familiarity (188-9). The article’s main claim is that

“each work denotes something, very often represents something, and the representation does not depend on the real existence of the represented object” (190).

This notion of landscape representing emotions subjective to the interpretation of a viewer and its impact on defining character identity can be found in The Complete Persepolis, This One Summer, and Happiness.

Bleed page landscapes in comics

Bleed pages of comics create the ideal format to represent the connection between landscape and the possible self by presenting this restructuring of self-identity in a timeless moment. In Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, he discusses the importance of the implied duration of scenes, where the content of a panel offers no clues to how long is spent in that moment (108).

He states that a panel whose nature seems unresolved—as in, the time is not definitive—may stick in the reader’s mind for longer and its presence may follow into future panels. Furthermore, he states that the additional use of a bleed page, where an image runs to the edge of the page without a border, compounds this effect as the scene “hemorrhages[sic]” into a timeless space not bound by the page (109).

Bleed pages effectively disrupt a comic’s dependability on time by removing the past, present, and future concept of the page. The bleed page is all and none at once. In The Complete Persepolis, This One Summer, and Happiness, bleed pages are used to signify to the reader the importance of these scenes by creating a timeless moment for readers to comprehend the connection between landscape and the possible self.

The Complete Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

The Complete Persepolis is an autobiographical comic following Marjane Satrapi’s life during and after the Islamic Revolution and explores her identity—and how she finds it—across different landscapes. Marjane narrates her way through time, from her childhood to her adulthood and explores her personal struggles with identity. From her struggle to adjust to the Islamic Revolution, to her struggle to adapt to life in Vienna, Marjane’s identity is consistently in conflict with the environment around her. In many key scenes wherein Marjane’s understanding of herself, her family, her values, or her country are tested, there are moments that seem to freeze the story to highlight this restructuring of self-identity with her landscape. One such page appears in the sequence after Marjane learns that her uncle, Anoosh, was executed for being a Russian spy.

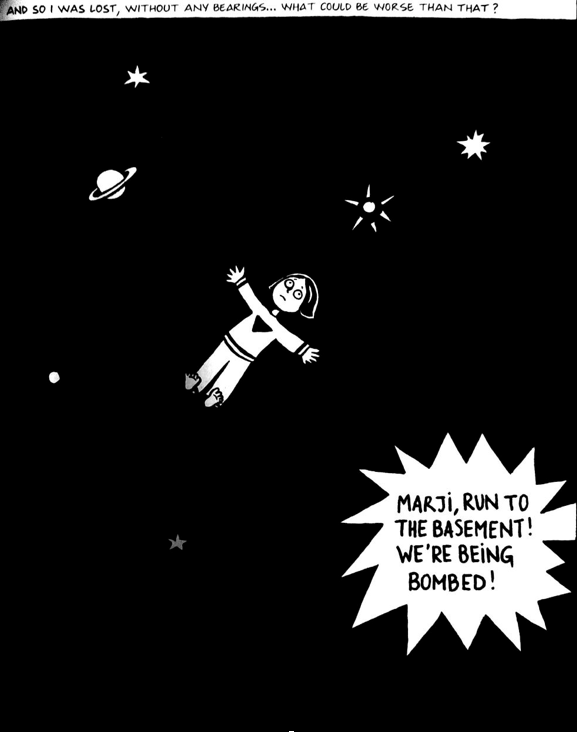

The final page of the chapter ‘The Sheep’ demonstrates the emotionality of the restructuring of self-identity by connecting Marjane’s possible self with the landscape surrounding her. The page is an almost-bleed page, because it achieves the result of a bleed page yet includes two line of narration, one at the top and one at the bottom-right. The first narration line opens with the words

“and so I was lost, without any bearings… what could be worse than that?” (75).

As your eyes scroll down the page you see Marjane laying on her back—an allusion to her laying on her bed on the previous page—arms spread wide in the midst of a black background which bleeds to the edge of the page. Sparingly dotting the page around her is a Saturn-like planet and a few stars. Slightly lower is a spiky dialogue bubble of someone yelling at Marji to run to the basement as they are being bombed. The last thing a reader notices on the page is the small narration on the bottom-right in a contrasting white box with the words

“it was the beginning of the war” (75).

Fig. 1. Satrapi, Marjane. The Complete Persepolis. 2007, p. 75.

The bleed page highlights Marjane’s restructuring of self-identity and alludes to the understanding of her possible self. In the page before, Marjane had learnt of her uncle’s execution and denounced God, telling him to “get out” (74), thus ending in her “feeling lost” (75) with nothing to anchor her to the world. She both lost her uncle, who she seemingly adored, and her faith in god. Her identity as an individual began to shift as she spread out across her bed.

The use of outer space as a landscape to show one feeling lost is not a new phenomenon; but it is a landscape that accurately presents this emotion to readers. The bleed page creates a timeless moment wherein Marjane seems frozen, staring out into space as she ponders her belief systems. As readers, we subconsciously understand that Marjane is not simply mourning her loss of her uncle or her denunciation of God, but that she is re-evaluating herself.

She is not simply pondering what has happened, but what may happen in the future, and what else she may experience. This connection between the reader’s conceptual understanding of what the landscape represents, the emotions connected to it, and the concept of Marjane’s restructuring of her possible self connect to create a scene of implied understanding between the reader and the page.

This One Summer, Mariko and Jillian Tamaki

This One Summer is a coming-of-age story featuring two teenage friends navigating their developing personal identities in relation to their holiday landscape: a small beachside town called Awago. Rose, the narrator and main character, and her friend Windy battle with family issues, sexuality, mental health, and the nuances of youth through their annual summer trip.

As the story progresses, the girls can be seen reflecting on their own identities past, present, and future, and as individuals they begin to pay more attention to the lives of the teens and adults around them. The two girls are no longer young children and are transitioning into the often complicated and emotional life of teenagers.

Rose and Windy are consistently contrasted with or placed within specific landscapes of Awago that represent and demonstrate their restructuring of self-identity. This is explicitly noticeable after Windy points out to Rose that her comments about a local pregnant girl are sexist.

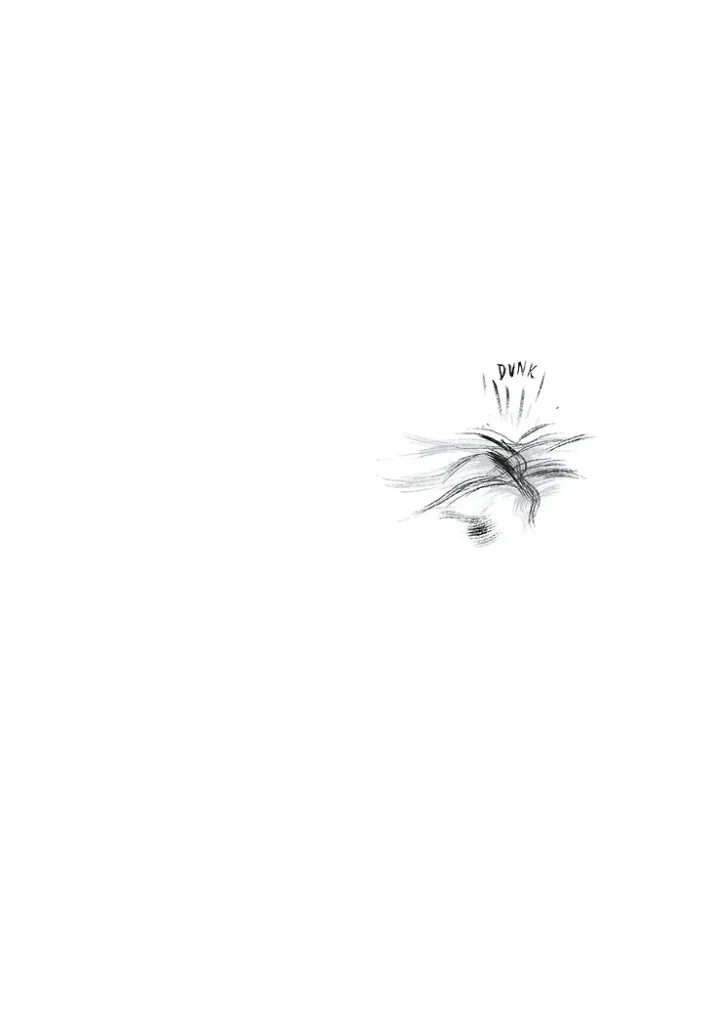

Page 245 of This One Summer demonstrates Rose’s difficulty accepting her possible self by using the landscape to represent erasure of self. Page 245 is dependent on the scene and pages that came before it, in which Windy denounces Rose’s slut shaming of a local pregnant girl and where Rose silently contemplates the fight by continually dunking her head underwater.

The authors remove the borders to create a shockingly empty bleed page of all white. Slightly off-centre is a sketch-like illusion of water and the word “dunk”. Rose herself is not featured on the page, but the illusion of her is. As readers, with the context of the previous pages, we know that Rose is dunking up and down in the water. The small circular wave of water depicting Rose dunking below the surface is alone on the sparse bleed page of white.

Fig. 2. Tamaki, Mariko and Tamaki, Jillian. This One Summer. 2014, p. 245.

Page 245 of This One Summer demonstrates Rose’s difficulty accepting her possible self by using the landscape to represent her erasure, whilst simultaneously cleansing her of the emotional baggage of self-knowledge, allowing for a renewed self-identity.

This clever use of a small portion of Rose’s landscape, and not the entire ocean, both connects the ideas of erasure and cleansing in a reader’s mind. When Windy called Rose’s words sexist, Rose was shocked and seemingly mad, and her perception of herself is visibly shaken. Feeling abandoned by Windy, Rose begins dunking up and down in the water. Rose questions her self-identity and the beliefs she held in herself and uses the water to physically wash away this version of her possible self, whilst also erasing herself from the moment.

Rose wants to forget this moment in the water, yet her restructuring of self-identity and her possible self is dependent on the acknowledgement of this moment. This connection between landscape and possible self alludes to a number of nuanced emotions one may experience when they feel as though they have done wrong, without needing to explain these feelings to a reader.

Happiness, Shūzō Oshimi

Happiness is a dark fantasy manga series that explores the concept of identity as the main character, Makoto Okazaki, begins to transition into a vampire. Okazaki is a bullied boy who struggles under the high school hierarchy until he is bitten by a mysterious female and begins to transition.

The manga series explores Okazaki’s changing self-identity by contrasting him with his environment, often using expressionist art styles that distort landscapes and reality to portray Okazaki’s struggle with his human and vampire sides. One such page appears in the chapter “Metamorphosis” as Okazaki deals with his hurt friend, his growing desire for blood, and his struggle to avoid Nora, the vampire who bit her.

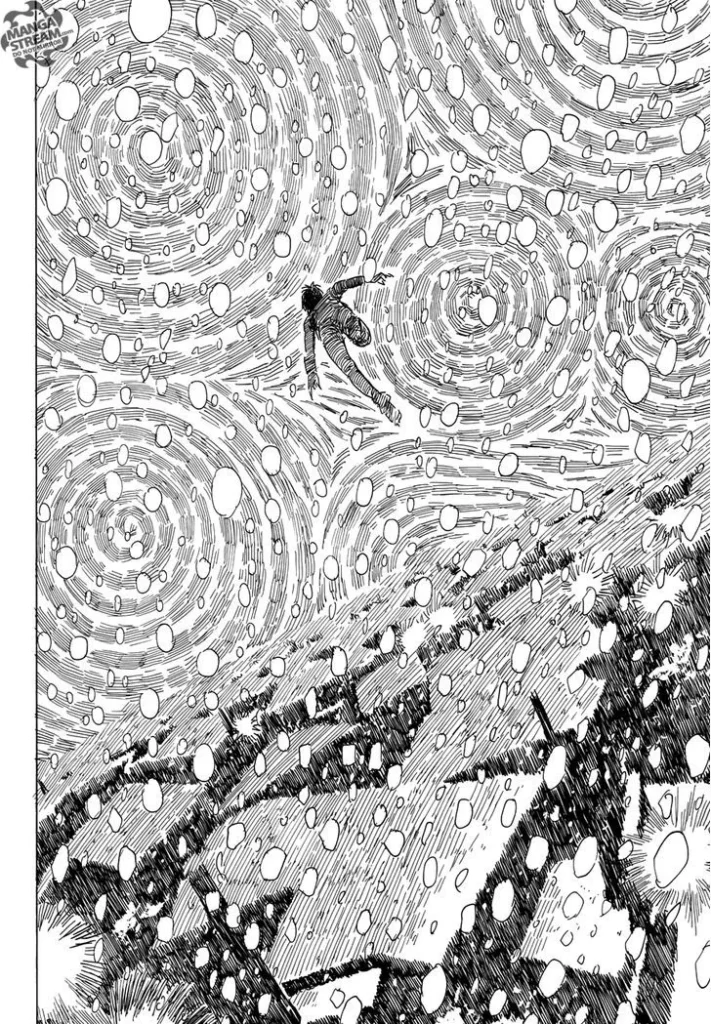

Page 37 of the chapter “Metamorphosis” uses a bleed page to freeze Okazaki in the moment of transition into the possible self he has been avoiding, and distorts the landscape around him to represent the mesmerising appeal of his possible self. There is a thin white banner on the left-hand side of the page, as though providing the reader a momentary break before the bleed page begins.

The page depicts Okazaki leaping from his hospital window and suspends him mid-air, slightly higher than the centre of the page. Suburbia covers the page below and distorts as though curving around the earth. Streetlights are simply jagged bursts that look like small explosions.

The sky takes up roughly two-thirds of the page and is presented in circular twirls reminiscent of Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night painting. Okazaki’s body leans counter-clockwise against the spinning motion of the sky surrounding him. Additionally, small and medium sized white circles are hastily drawn across the landscape, representing snow fall.

Fig. 3. Shūzō, Oshimi. Beyond the Pale. Vol. 3 of Happiness. 2015, p. 37.

This page from Happiness demonstrates the connection between landscape and identity by distorting the reality of landscape to highlight the confusing appeal of Okazaki’s possible self. The use of illusion-like swirls as the sky shows the appeal of Okazaki’s possible self and the confusion it brings him.

Although he consistently fights against his new desires and feels a loss of his human identity, he still leaps into the sky. This landscape minimises the suburban lifestyle he is leaving and maximises the appeal of the night sky, a landscape consistently represented throughout the comic in connection to his vampiric self. The use of the white border provides a break in the scene, as though there was a slight hesitation before Okazaki jumped out of the window.

The reader views this page and this moment as a defining transition for Okazaki wherein he is no longer leaning toward his human identity, but beginning to accept this new possible self he hides inside—his vampiric self. This allusion to the possible self and the hopes, fears, worries, and dreams one has for themselves and their identity in the future is one of Okazaki’s prominent conflicts throughout the novels. This scene perfectly encapsulates the way landscape is used to represent and support his conflicting identities in relation to the self he is afraid of—his possible self.

Conclusion

This essay discussed the connection between the possible self and landscape, arguing that the connection of these two creates and implied understanding of transition for the reader. Theories on bleed pages, the possible self, and the representation of landscape were discussed and referred to throughout the analysis of three comics: Marjane Satrapi’s The Complete Persepolis, Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’s This One Summer, and Shūzō Oshimi’s Happiness. Each comic was discussed regarding their connections to the essay’s argument, before one bleed page from each was described and analysed. In conclusion, this essay found that a connection between landscape and the possible self creates an implied understanding that a character is undergoing a moment of transition in their self-identity.

Works Cited

Markus, Hazel, and Nurius, Paula. “Possible Selves”. American Psychologist, vol. 41, no. 9, 1986, pp. 954-969, doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954. Accessed 26 October 2020.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper Collins, 1993.

Sarapik, V. “Landscape: the Problem with Representation”. Koht ja Paik / Place and Location II, edited by Virve Sarapik, Kadri Tüür, and Mari Laanemets, Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Arts 10, 2002, pp. 183-199. www.eki.ee/km/place/pdf/KP2_12sarapik.pdf. Accessed 26 October 2020.

Satrapi, Marjane. The Complete Persepolis. Pantheon Books, 2007.

Shūzō, Oshimi. Beyond the Pale. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2015. Print. Vol. 3 of Shūzō Oshimi’s Happiness.

Tamaki, Mariko, and Tamaki, Jillian. This One Summer. First ed., First Second, 2014.