The streets of Shibuya have been seen by many people, not just in person but in movies, photos, and TV shows. There’s an odd sense of allurement connected to those streets. The unique architecture style that is boxy yet not modern is instantly recognisable—not as a trait solely of Shibuya, but as a trait of Japan. If you walk far enough to the edge of the ward, then you will find yourself away from the fluorescent advertisements, ringing music, and continual hum of chatter that permeates the air near the scramble crossing.

The edge of the ward is quiet; The streets die down and I feel less like I am in the heart of Tokyo and more like I am in a neo-noir movie. Lights reflect off the white lines of the road as I stand in the drizzling rain under the safety of a pink umbrella. I’m holding a plastic bag full of assorted canned alcohol from the convenience store that cost me less than ten Australian dollars. It was then that I realised what I wanted in life.

In 2019, I travelled to Tokyo for a two-week study tour with my university. When I tell people about the trip, they ask me what it was for. I feel like that is an unusual question to ask—what is anything for? It was a trip to Japan, it went toward my degree, I’d always wanted to go, and the government provided a three-thousand-dollar grant. I typically replied with ‘why not?’.

Organising the trip wasn’t a fun one. I had no savings at the time (at least, not enough to buy the plane tickets), so while everyone else was getting great deals and cheap flights, I was waiting for the super-cool grant to be deposited into my account. By the time it did, I ended up paying an extra four-hundred dollars for the exact same flight as my peers. Well, it wasn’t my money though, so I wasn’t too mad.

I didn’t know anyone going on the trip with me. When we first got accepted into the program, we were told to begin chatting with one another and discussing flights, accommodation, you know, get to know one another. Our supervisor told us his hotel and said we could book there. The university paid for his room in a fancy four-star hotel that was a two-minute walk to the nearest train station. Two weeks would have cost four-thousand dollars. Only two girls stayed there with him, but they said their parents forced them to.

I wasn’t sure about much heading into that trip—including myself—but I was sure about how I was going to get around and where I wanted to stay. The first one was easy: I ordered a train pass (I chose the Suica card) and sim card that got posted to my house in Australia two weeks before we left. I was positive that I didn’t want to be stranded in the airport lost, not knowing enough Japanese to get to my accommodation. I also didn’t want to find myself in a different country without the security of Google Maps in my pocket.

As for the second, my requirements were that it had to be cheap (around two-thousand-dollars for two weeks would be ideal, finishing off that grant money), it had to be in a cool area with lots to explore, and it had to be a hostel. Most people hated hostels but if I knew two things back then, one was that hostels were cheap and the other that hostels meant people. People of different places, cultures, languages. People who were willing to meet other people. You don’t stay at a hostel if you want to be alone.

I booked a cubical in a twenty-eight-bed mixed dorm hostel and read enough reviews online to know I wanted to be as far away from the door as possible because of all the late-night comers and goers. It was on the edge of the Shibuya ward. Close enough that I could walk to the scramble crossing but also far enough away that I wasn’t disturbed by the crazy night life of the area. The best part? For sixteen nights, it cost me two-thousand on the dot. It was cleaner than I thought it would be, and newer too. I told my peers about the great deal via email, but only two males were brave enough to join me. Spoiler alert: we all got sick. Twice.

The hostel had polished concrete floors with scratched metal skirtings, white linen, and wooden tables, giving off the perfect minimalist industrial vibe I expected from Tokyo. It had green vines curling around the furniture to soften the environment, and a large wooden owl that hooted and moved its wings when you walked in front of it. It was called ‘The Wise Owl Hostel’. There was a bar in the reception and three different convenience stores across the road. Every night, the owner would sit and play his guitar on a small couch, setting the vibe for the guests as we drank and mingled before heading into Shibuya. It was an expectation that if you sat at the bar, you were wanting to chat with someone. I met someone new every night.

My first night there, I met a man called Tom. He was from Texas and he slept on the bunk above mine. His accent was so thick that I had trouble understanding him but at least we were speaking the same language. We didn’t talk often, as our schedules were very different. I was there for a diligent study tour, which meant I had appropriate bed times of 1am, wherein he would stumble in at 5am. Although, he did have a few early nights in preparation for his climb up Mt Fuji, but I didn’t see him again after he left for that.

Two nights after our first meeting, I was out clubbing. It was a fun night. The best I’d had! We were at a five-story night club, and I’d just been pickpocketed (luckily only losing one-thousand yen, about the equivalent of AUD$15). In the meantime, Tom projectile vomited down the stairs from his bed, past mine, and all the way down the hall to the bathroom. I found out three days later when he said sorry for getting some on my suitcase. Like I said, the place was clean. I hadn’t even known.

Another day, I was eating my breakfast from the convenience store when a Japanese guy came to sit at the table next to me. He was short and muscley, like a wrestler. I said hello first. His name was Yuya. He was from Tokyo but had been studying at university in California. He’d flown back for a job interview. We spent the entire day together and he showed me his favourite café. He quickly became a member of my little group of hostel friends who went out for dinner every night, and he showed us his favourite local izakaya. Since he was fluent in Japanese, he helped us solve any miscommunications and we got turned away less for being foreigners. We still talk every so often, and he’s waiting for me to return so we can have another drink of sake together.

I also met a cool guy from the UK, who was tall and funny and had the most beautiful melanin-dense skin. To this day I can’t remember his name. I see his anonymous posts on his food-focused Instagram and remember he wants to be a chef, but his father isn’t supportive. He had a girlfriend in Tokyo who broke up with him the day he flew in. That’s how we became friends—he had been drinking in the lobby of the hostel and looked lost. It was one of those moments where you see someone who has had all of their life sucked from them. Alcohol in hand, dead eyes, a melon bread in front of them. I’d sat down near him with my own drink and said hello. I have a drunk video of us at the Shibuya scramble crossing doing the cha-cha. We don’t talk any more, but I always think his food looks delicious.

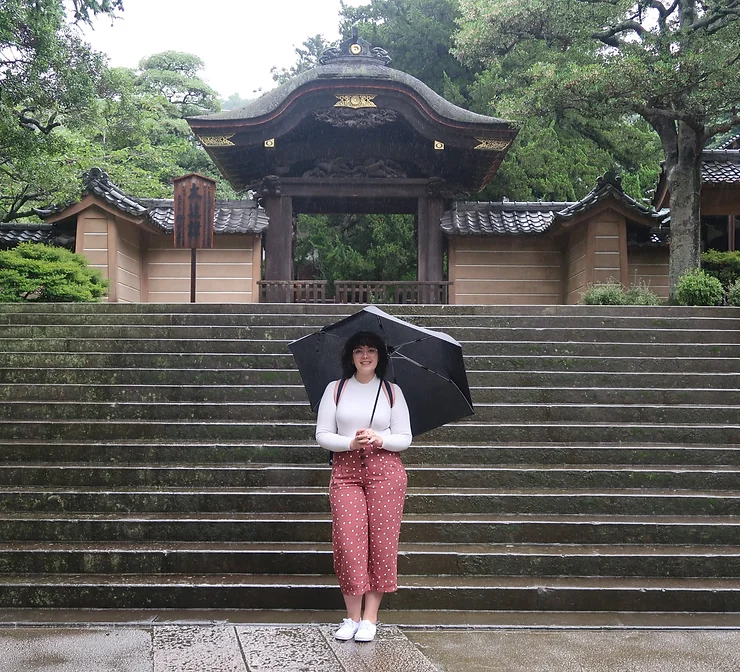

I also met three Korean Americans from New York who slept two bunks down from me. I think I talked to them first in the lobby, but I can’t remember exactly now. One of them was called Johnny and we got along especially well. We would often be caught chatting wherever we ran into one another—at the bathroom, at the foot of his cubical, in the hostel elevator. One weekend when my study tour friends were too hung over to do anything, I joined Johnny and his two friends on their way to Asakusa. We wore yukatas, a summer version of a kimono, and rode rickshaws together to different shrines. We went and bought matcha tea and matcha-covered nuts. The photos the rickshaw drivers too that day remain my favourite. I still talk to Johnny online and we organised to meet up in Seoul, South Korea, where he now lives and works. It’s been postponed for when COVID-19 settles down.

The dorm in Shibuya was a risky move. It could have been dirty, old, too loud, or maybe I could have ended up with a weird bunkmate (although Tom nearly fit that bill). Yet, it turned out to be the best part. Being in Japan was a fun experience, but it was the people I became friends with and the new perspectives on life that they gave me which truly helped me. There are countless other individuals who I crossed paths with and barely remember: an American girl who gave me an expensive pink umbrella as she left the hostel, a French woman who I smoked my first cigarette with, a British guy who gave me all his left-over money. People who I didn’t spend time with, but who impacted me. For the entire trip in Japan, I’d been struggling with one thing—my identity between who I thought I was, who I wanted to be, and who I was forced to be at home. Although every night was a great night, that night is stuck in my head the most. That night under that pink umbrella in the rain. That moment of clarity as though I’d just hit a checkpoint in life. A romanticised moment of Japan, but one that clarified my being. I took my bag of convenience store alcohol and walked to a nearby park, where a number of locals sat beneath a gazebo and drank. I joined them, and as we drank away the night in the rain, it felt like I’d found the part of me that had been lost—the part of me that desperately needed the trip.